Value-Oriented Testing

The Current State of Things

“Code coverage, 80%!” is the mantra we hear. It has a balanced philosophy: achieving 100% code coverage is unlikely (as not all code is easily testable), and ensures that enough of the codebase is tested that bug-bashing confidence is, well, 80%.

Every measure ceases to become good once targeted is what I would say, if code coverage wasn’t clever. It’s difficult to game the number, aside from writing irrevocably dense code. But it is still a hard number, and hard numbers are picky. What if your PR hits 79.9% coverage? What if it’s 77%, but you fully tested your addition — the miss comes from the previous PR eating up the previous 84% down to 80%.

Does that sound contrived? Well, it is! So let’s build a more coherent argument versus relying on cherry-picked experiences the author has had very vivid dreams/hallucinations about, but have absolutely never occurred in reality.

What’s the point of testing?

To build confidence!

Tests are not a “sake of best practice”, and I believe treating them as such robs them of their primary benefit. The sweet air of a green checkmark is a calling to you. It sings that your newly-added/deleted/modified code maintains functionality, and — if you added tests — that your code is itself protected with that same grace. Rip out that ViewModel from 3 years ago. Why not? "Because it will break something"? Well, the tests passed. Tests passing indicate it won’t break something. The hypothetical fear of "might" break has been proven to be false.

Unless.

Unless the tests aren’t covering the right thing. Unless the tests didn’t hit that one teeny code path that trips unexpectedly, because it was only a small % of code, and we weren’t searching for 100% coverage. Unless the tests looked like they covered functionality, but — much like a calculator app that compiles, but says 2+2=22 — the logical result is not enforced: only the rough semantics of types, names, and patterns are enforced.

Also, building confidence is nice and all, but its success story is defined by a reduction in bugs. We can be happy worker bees galvanizing the service layer like there’s no tomorrow, but tests build confidence that regressions will not crop up unexpectedly. The fuzzy feeling is deterministic.

We’re also human (as of writing). Even if we figured out a perfect system, a bit of wiggle room would be good alongside the entropy of being human (as of writing). We need a measure of reliability. A measure of “when are we confident enough in our testing”.

Oh. I did say that.

Oh, I did say that.

Let’s try a new framework instead. Something something proving the contrapositive.

-

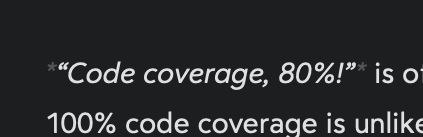

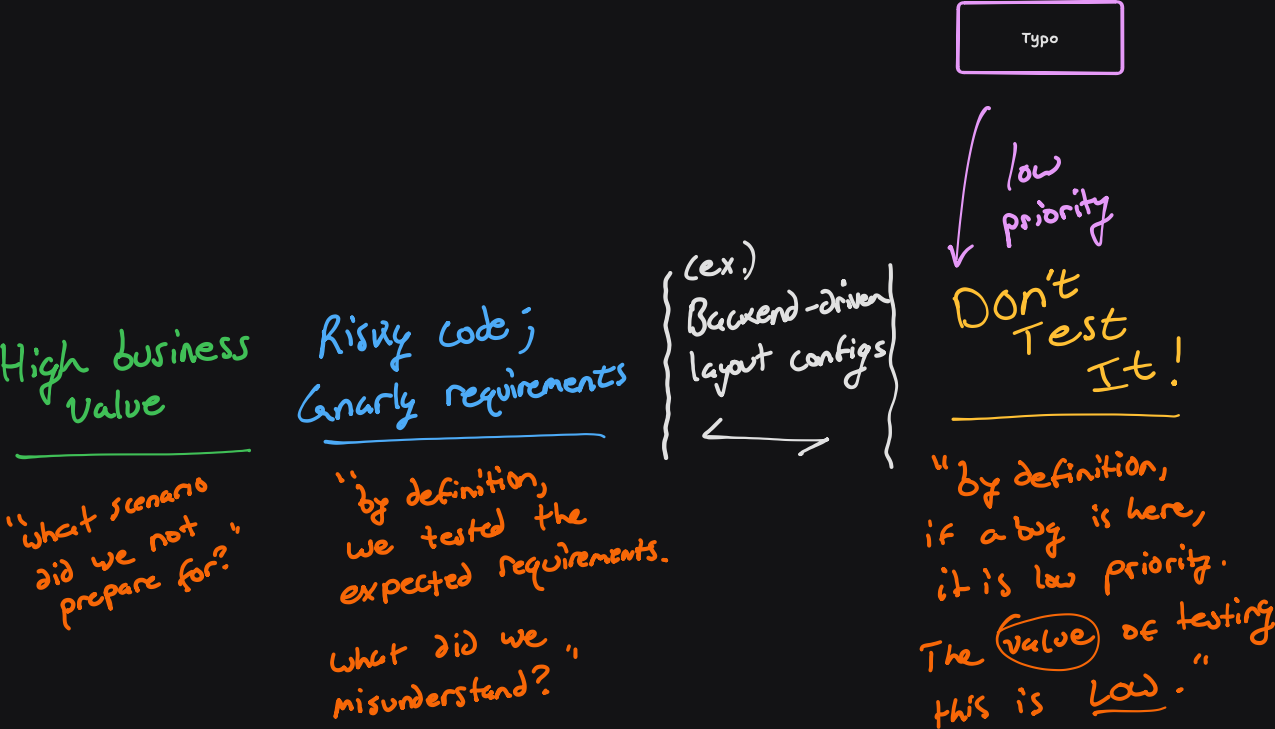

First, test the high-business-value paths.

This includes auth, billing, support — whatever keeps the lights on, shareholders happy, provides the value your product intends to deliver. If the phrase “can’t break” is used, that’s a great indicator that it falls in here. -

Test risky/complicated code, or requirements that are tricky to grok.

Sloppy code happens. An engineer who just learned template metaprogramming happens. A 2,153 line PR on a Friday afternoon happens. If a bug comes in, solving the bug usually requires understanding how the code works in its existing state. By definition, if it’s hard to understand, a bug fix will open the proverbial spaghetti box to throw on the wall. Not great.Tests define the existing and expected behavior! Plus, “write tests” is an easier, objective ask than “write this to be more readable” — a platitude that is somehow low priority, which tends to get ignored.

-

A free category to allocate depending on your team’s time budget

Does your app have a backend-driven modular layout? Do you depend on one-shot events like livestreams? These are good specific cases to identify, but keeping this lean is a good idea. A tight deadline shouldn’t come with a huge checklist of required tests to write, in which case, we’re back in 80% coverage land. -

Otherwise — and stick with me here — don’t test it.

This gives us a very interesting flow of responsibility. Let’s look at some scenarios!

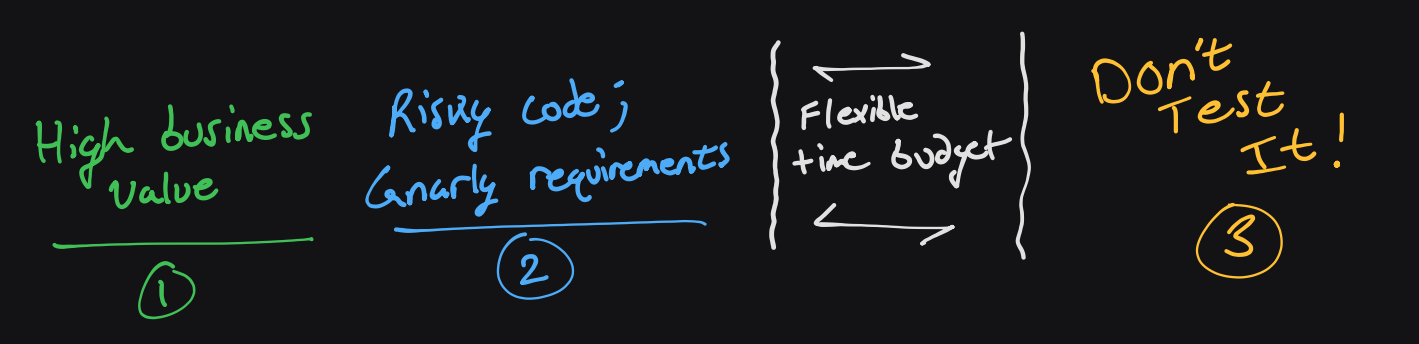

- A bug comes in for a broken layout on the support page. This is high business value, as if users can’t contact support, they can’t get help. Things that are business critical deserve the time to think out contingency plans. If an unexpected issue occurs, it’s likely not with the implementation, as the behavior was verified in tests. Rather, the issue is unexpected — that scenario needs to be handled.

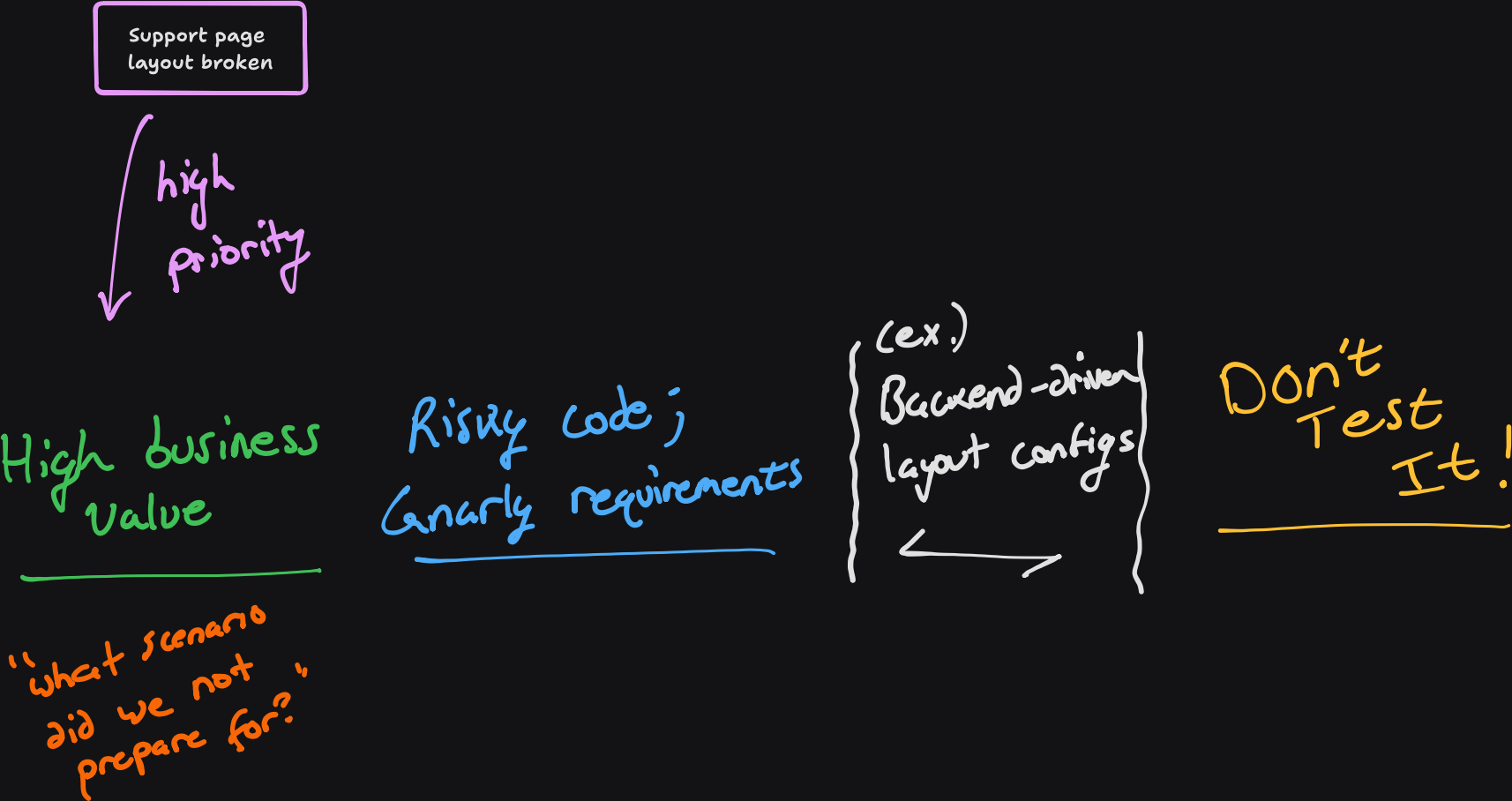

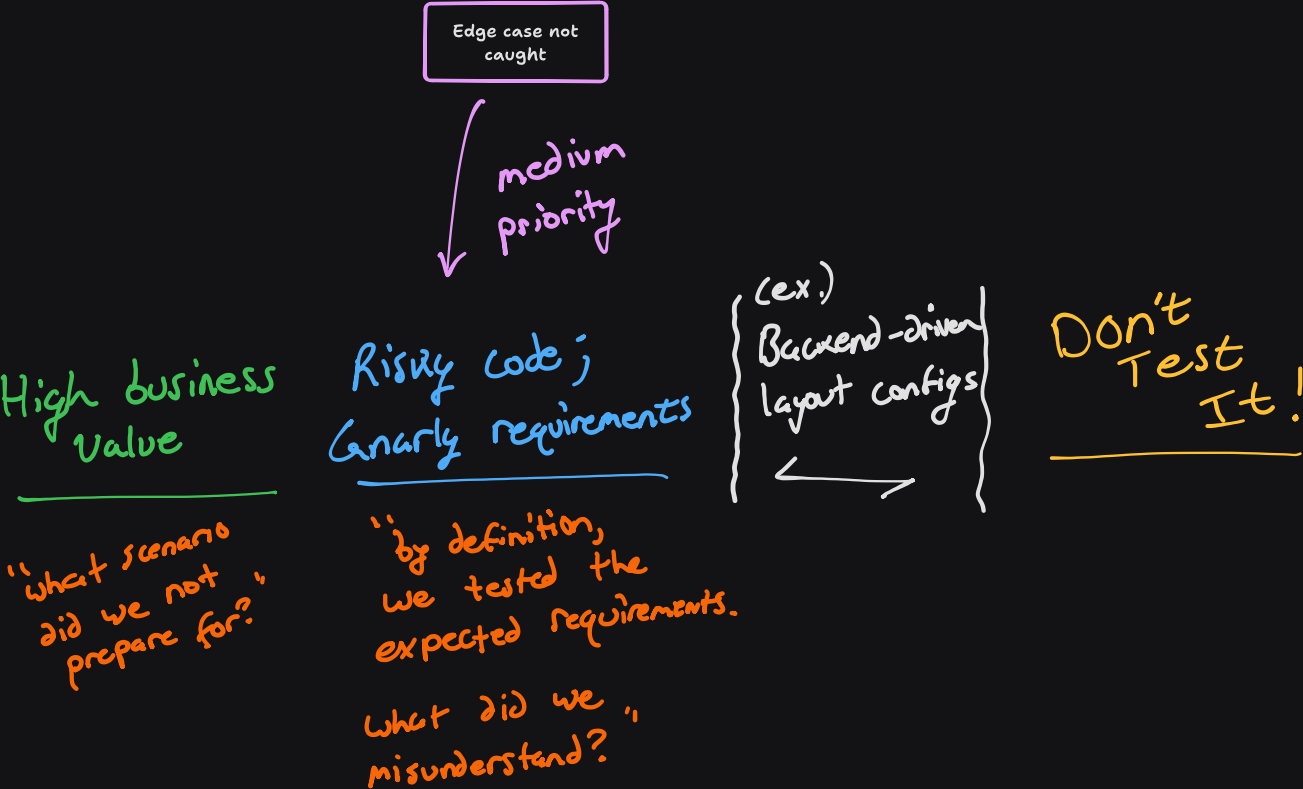

- Bug: The settings page for adjusting the user’s selected time zone errored out. This code is complex (various edge cases w.r.t. the system time zone vs. the user’s preferred), and the requirements are tricky (daylight savings, time zones off by 00:30min, geolocation via IP when the user is on a plane, etc.). By definition, the tests are 1:1 with the defined requirements, as this was identified as a source of risk. So, what happened? Did the error fit within our expected understanding of the requirements? Did the code reach a logical error despite hitting 100% localized coverage? Did the engineer misunderstand the requirements? These questions help prevent misunderstandings in the future, and grow craft in engineers’ ability to cover these scenarios more holistically.

-

(I’m skipping over the team-defined case for brevity, exercise to the reader, margin is too small to contain this marvelous explanation, etc. etc.)

-

A typo is found in the app’s theme selection page. This is low-priority, it’s rare that it happens (given multiple developers+QA looked at this screen, plus dogfooding in % rollouts). The likelihood that this occurs a lot is low, so the calculus to write monotonous copy tests doesn’t work: the juice is not worth the squeeze. That effort is better spent developing a robust and resilient understanding of the other 3 categories.

The Takeaway of Value-Oriented Testing

Writing tests in priority of value results in tests that are inherently valuable. A test — “extra work” that isn’t tech debt or a new feature — is never wasted, as it is applied based on the inherent risk of that code failing. Conversely, tests now enforce confidence for domains that require it. While it might be nice to catch UI imperfections in CI/CD, that confidence is only needed if the risk of it breaking is high enough.

In less words: write tests, a.k.a. build confidence, in the parts that matter. You now don’t have to worry about breaking the parts that matter. And don’t worry about the parts that don’t matter :)